Following New York’s recent release of teacher rankings, the chatter in the education community has once again focused upon an old question: is it wise to evaluate teachers based on student performance on standardized tests?

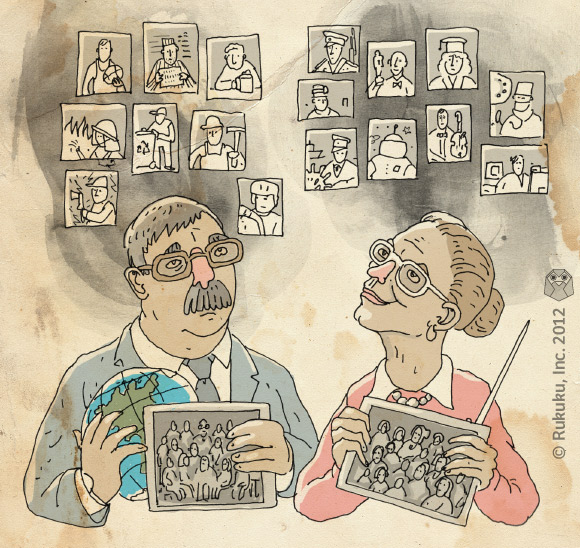

Simplistic political demagoguery aside, teacher accountability is actually a complex issue. Children in different areas and of different backgrounds are subject to different circumstances, capabilities, and opportunities. Mandating one-size-fits-all standards to an endlessly diverse body of students and educators is great at making politicians seem tough, but very bad at improving the quality of education.

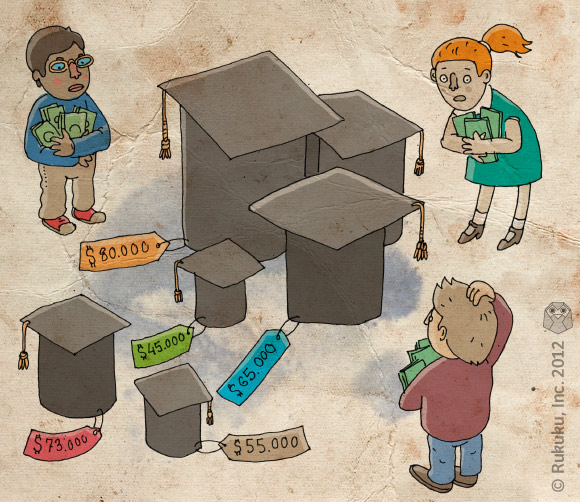

The entrenched standardized evaluation system also creates the phenomenon of “teaching to the test” – that is, educators focusing all their efforts on ensuring that students are able to answer formulaic test questions rather than learn in a meaningful and permanent way. The incentives created by standardized testing are all wrong: teaching students how to fill in circles with a number 2 pencil is rewarded (a la Monday’s comic), while showing them how to think critically, be creative, and learn with real depth is discouraged. This is, by the way, to say nothing of the rampant teacher cheating that the system invites.

Sadly, the stories of the machine’s latest victims – New York City’s teachers and students – seem unlikely to meaningfully diminish the bureaucrats’ heavy-handed influence on education.

The fact that local school boards and the DOE continue to defend rigid educator evaluation based on standardized testing shows that today’s educational bureaucracies are totally out of touch with reality (at best).

For years, it has been plainly obvious that standardized tests are a dreadfully inadequate way of measuring how much students have actually learned. It should follow, then, that using them to measure teacher performance is downright stupid.

Why on earth are we still doing this?