College is a great investment. Graduates from bachelor’s programs earn about $500,000 more during their lifetimes than peers with only high school diplomas. In fact, even those that go to college but don’t graduate will get around $100,000 more in lifetime earnings than high school only graduates, according the DC-based Hamilton Project, which is part of the Brookings Institution. In a June study, the group concluded that investment in a college education offers returns two to three times higher, on average, than those from investments such as stocks, bonds, gold, treasury bills, and housing.

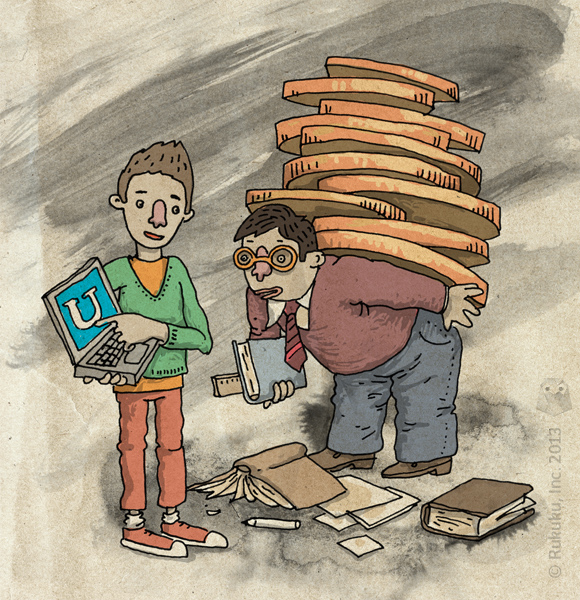

Young graduates struggle to stay ahead of their student debt payments

Still, college is expensive, even if it is a good investment. And it is getting more expensive. Educational costs rose 165% from 1993 to 2011, more than broad inflation and medical care costs, which were up 56% and 100% respectively, according to Emily Dai of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Several factors are involved.

One is that, once upon a time, most people that worked at universities were in the classroom teaching. Nowadays, there are more administrators, vice-provosts, assistant deans and chairpersons of committees on something or another. There are more researchers as well. A report from the DC-based Delta Cost Project showed that the proportion of education spending set aside for instruction decreased from 2000 to 2010, with costs related to research, student services, academic and institutional services all growing more quickly. Student-to-teacher ratio has hardly changed in thirty years.

Schools are also spending more money on facilities that will attract quality students and well-known professors. That sounds reasonable. Everyone wants good students and teachers. At the same time, I am not sure if you want your students to stay because of a nice swimming pool. Well, except that if they drop out, or even if they get accepted but decide not to come, that affects your school’s ranking in the college books and magazine ratings.

While spending has gone up, financial support at the state and local levels has dropped off significantly. Most universities have tried to fill the gap, or at least some of it, with higher tuition. In 2010, for the first time ever, tuition contributed more toward education expenses at public research and master’s institutions than local and state government appropriations, according to Delta.

Luckily, or sort of luckily, there are many programs to help students pay for school, including scholarships, grants, loans, and work-study programs. Most students, 71% according to the Department of Education, receive some form of financial aid. Forty two percent take out federal student loans.

Those loans can easily be repaid once these students are all out in the real world and making big bucks. Only that doesn’t always happen. As it turns out, not every business venture needs a philosopher (my major, by the way). Few 18-year olds truly understand the amount of risk and responsibility they take on when signing those loan papers. Many of them don’t know to separate colors from whites in the laundry either.

With this in mind, it is easy to draw parallels to the conditions preceding the mortgage crisis. Abundant credit is readily available to inexperienced buyers, a situation which feeds market bubbles. In real estate, we know how that story ends, or least the most recent chapter. Housing prices inflated, then popped, wreaking havoc on the national economy, then the global economy. In the case of education, it is the tuition prices inflating, and we don’t yet know the consequences. In other words, student loans, which help individuals go to school, are pushing up prices for college attendees as a whole.

Emily Dai of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank explains, “A college education, like home ownership before the financial crisis, is increasingly viewed as a social good – but one that could quickly become a liability. And the maximum federal loan amount available to students continues to increase, underpinning the fear of the size of the potential liability.”

Defaults are already rising. A study released from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau earlier this month finds that almost one third of all federal borrowers are in default, deferment, or forbearance.

Nationally, outstanding student debt now totals more than $1 trillion, doubling since 2007. That total is still less than mortgage debt, but more than outstanding credit card debt or automotive debt. And it is more difficult to escape than credit card or mortgage debt as well. You can give a house back to the bank and declare bankruptcy for most other debts, but that won’t erase student loans.

In our next post, we’ll look at some of the effects this debt has on young graduates.